|

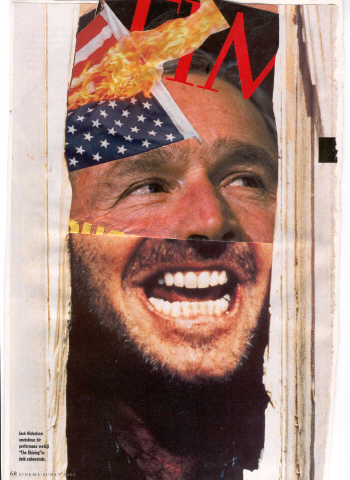

[My new favorite writer of late has been Denton Welch -- I've read both In Youth Is Pleasure and A Voice Through A Cloud in the past month. I have a bad cold, however, so outside of providing this caricature that I found online, I'm just going to have to paste some prose I had found on a Denton Welch fan site that gives a pretty accurate description of what it's like reading him.

Burroughs was a fan, as was Edith Sitwell and W.H. Auden; Rod Smith also wrote about him in Rain Taxi a few years ago. Welch reminds me most of Rimbaud, though, especially in In Youth Is Pleasure -- some of these paragraphs are so well put together, and so full of imagistic detail, and he is so openn to all sorts of experiences -- ranging from the Tennysonian temper of his interest in ruins and castles, the Huck Finn-like taking to the open road, to the more Genet-like moments of putting on make-up or even self-flagellation just because it piques his interest to do so -- you think you're reading someone whose senses were just coming to life, and certainly he was quite brave to take on the responsibility of investigation.]

It would be difficult to find any more intensely cultural, or cultured world in literature than Welch's. His obsession with old churches, rambling gardens, ruling-class mansions, period furniture and all the smaller artefacts, like 'Gothic Revival toast-racks', that are special emblems of Englishness make him more English, more pre-War, and more literary in the Bloomsbury sense than any other writer of his time and place.

And yet what you will find in these excerpts, as in all of his work, is a highly-coloured, imagistic, raw and seemingly unsophisticated style that seems to invite ridicule, before the reader realises it is his or her own psychological defences that Welch's clear, factual voice has aroused. While its grammatical construction is precise to the point of sounding stiff to our ears, Welch's language continually stimulates because it is uncensored in terms of the private experiences it unfolds. The author is continually saying what is unsayable, even 'unthinkable' in daily social life, and the anarchic result is hilarious and moving.

Like Austen or Proust, Denton Welch achieves a surgical accuracy of description of the poltroons, wasters and fops of his own class. Few writers etch the vanity of human beings with too much money and too little experience so sharply as he. But in his writing there is also a frankness about his own oddities of mind that is disarming and deceptively easy to read (as it surely is not easy to write). A passage of Welch leads us to understand how charm can have a serious evaluative meaning in prose. It is a lesson in good style. It astounds me that a person whose social world was so rarefied and hermetic could write with such sensitivity to human suffering and with no sense of self-importance or pretence. Welch writes about human feelings and motivations with an unblinking candour that we associate with a Sartre or Camus: his gaze on the world is of such clarity that he leads me to wonder what the greats of French literature could have achieved if they, like Denton Welch, were never tempted into intellectual posturing.

[Here's a poem that recently appeared in the third issue of Pom Pom. I revised it today, it's a thousand times better, but I thank them for running the earlier version -- of course! Pom Pom is interesting -- it's premised on the idea that each new issue is mostly revisions of poems/lines from the previous issues -- you can download .pdfs of the first two issues on the site, and if you have any innovative ideas on how to rewrite/revise, then submit!]

Classic Snuff Pieces

Getting ready to have been

made to have felt

very awkward. Do you

mind if I sit on your leg?

Despair, confusion,

all those things

express themselves without words. Well,

you know the miracle.

To leave me

at home with my humanist musics

when I am humming, taking up themes

(the heavens pay attention to me)

couldn’t

I have the money first? Then

dialogue? I want

justice in the cards, in chance, but

only after lots of money.

Matriarchal sunnuvabitch type.

And they enjoy it

and call me Bob.

*

Classic

Snuff Pieces of Japan.

The first ones

to come up with a clear thought, yesss. Kind of

jazzed up for the end.

*

Sometimes, I don’t know

what I’m doing. I thought,

perhaps, that wasn’t her name

because

it rhymed. But

the seasons are fevered.

These days

we call it

Australian Rules Summer: the grossest reveries, a

plague on both noses, eye

link

black. Is anyone

playing as honestly as I?

Standing around in this

mesh of instincts

(but I wasn’t the first one to think of it).

I would have been happy to have been

teased by you.

As it were.

[Perfectly useless piece of news, but here's the cover to my new book. It's at the printers -- could be a matter of six weeks or so before it's alive. I decided not to use one of my own designs since I just wanted to get the thing done, and I think Ree came up with a nice, elegant solution -- it's (I fancy) in the "white series" of books such as Kenny Goldsmith's Fidget, Dan Farrell's The Inkblot Record, Steve McCaffery's two volume selected, and Christian Bök's Eunoia, etc.]

[Again, I'm at a loss for material for this blog, but I did find this crappy scan of an essay I wrote on Frank O'Hara sometime in the early 90s. I would have been, say, 24. It was written on an Apple SE, printed on a dot-matrix very lightly -- I scanned it in several years ago but never corrected it. But it looks just fine to me now.]

The Collected Poems of Frank OHara

1995, University of California Press, Berkeley

588 pages, paper, $18

Frank O’hara was one of the last poets to possess the great idea of liberty, one port-able enough for the whole city, for all situations and inconveniences, but which also knew the dangers of indulgence and lax attention. It was the liberty of the French po-ets, of Apollinaire and Breton, which bore on its shoulders a philosophy that argued against the possibility of personal agency, but which could also win the day, given en-ergy and a sense of purpose. CYHara did win the cfry, which is why one wants to go outside and see these poems in action. Some of them are like an entire season; however, rather than the famous sai~v~ of his great predecessor Rimbaud, they are seasons in zen” (sorry), meaning that the openness and inclusiveness of John Cage is there, too, with all its wealth of non-noise, hanging aphorisms, and Thoreau-like confidence among the wilds.

Ol-lara describes this cross of influ-ences with characteristic nonchalance in Tive Poems” (a poem that dldn’t appear in Donald Allens Se/ectedPoenis of Frank O7kra published in 1974, but which is included in this paperback reissue of Allens terrific collection from 1971):

~i invil*ion In lunch

H~i DOYOU LIKE THAI?

when Ionlyhwe l6centsand2

p~ka~s of yogurt

ttvjres a lesson in that, isnt there like in Chinese poetry when a leaf falls?

That lesson is contained in a number of OHaras best known poems, somewhere be-tween the construction workers, sandwiches, cheap copies of Genet and lonesco, in the voice of Billy Holiday or in a painting of Mike Goldberg~s. This excerpt contains the most famous elements of OHaras aesthetic in naked paradigm: the ubiquitous lunch, numbers (very Charles Demuth), the real concerns of a young poet in the city but also the victorious optimism. Trivial objects with a right all their own brush tq against “heavy” Chinese philosophy -- the vogue then, thanks to Pound, Rexroth and other surveyors of world culture.

In fact, much of O1-taras poetry can be seen as an arglinent against the self-importance of much of the aesthetic posturing in poetry at that time; after all, it was Pount2rs didactic urge and ability to assimilate cultures that led to his adoption of fascism. Ol-laras casualness, his ability to approach but not be disturbed by the various programs of American poets (in a New York that was populated by Europes most talented exiles) can be seen as the necessary breaking free from these pressures to dictate -- though, in the long run, OHaras “Personism” became as influential as any American manifesto for the arts, especially in New York. Ol-lara had numerous heroes

-- Pollock, DeKooning, his friend Jane Freilicher, Picasso and Matisse -- but none of them were cast in the “hero and hero-worship” mold, demanding emulation. “Picasso made me tough and quick, and the world” 01-tat-a writes in an early poem, and he followed his heroes with a secret understanding (or an understanding of their secret), not with futile reverence. He could even disarm with one line a theory that threatened to replace the personal with abstraction (in this case Charles Olsons) as when he writes (in “Hotel Transylvanie”) “Where will you find me, projective verse, since I will be goneT

Which means that you can be perfectly g1oon~y and read OHara, too; he knew how to move among and excite the tangle of constructs that are, generally, ones strength and burden: the personality. He was one of the few poets who could use moods as material for art, and his aim is to disturb you into self-possession, and into enjoying it if he can help it. “In the beginning there was YOU -- there will always be YOU, I guess,” reads one of his “Lines for Fortune Cookies”; it is when he combines this ability with his startling ear, his endless supply of new forms for poetry and his sure sense of languaqe that one is, well, floored:

hook

at you and I wouhi rather look at you than all the portraits of the worhi except p~sibly for the Polish Riih oc~osionaI ly mid anyway itS in the Frick which thank hesyans ytiu havsi t pine to yot so we can gu to~ther the first time mid the fm~t that yw move so bewatiful ly more or k~s tokes care of Futurbn just as at hmne I never think of the Nii~DexewikrgaStafrcase

frem “HavinqaCoke With You”

Ol-tara looked at art and life through the same pair of eyes; if that sounds obvious, consider that this poem, which is basi-cally high caliber talk, is Surrealist in both its being “automatic” writing of sorts, and in its use of montage techniques to trace weird, geometric narrative patterns -- going from “you” to the Polish ft’kkf, then zooming into the Frick and back out again in two lines, ending up at home thinking of Duchamps painting (itself about lay-ered time) which has, however, already been annihilated by 01-tat-as, what, hyperbole? He is sure of where art stands in his relationship with the world; it is tense but easy. A sketch of an entire relationship --who lives with whom, what they have seen, etc.-- at-tentive to both its trivialities and granch.ier is expressed in these lines, in what is gen-erally not a “psychological” poem; John Berrymnan should be so skillful. The poem seems to have been written for two people very successfully -- which is one more than usual -- 01-tat-as special brand of postmodern “transgression”, taking the poem into the personal (and the person to whom it is written) so much that it. is nearly transparent.

largely unphysical

questions remained

in the blond curtain

fluxions of cement

we've had enough with

and there, gesturing

with indrawn talons

fair, antiquated form

of farcery circumvented

rushing lingo intrudes

loneliness will make it cohere

a stand against vengeance

that's largely speculative

my ordered, ordered princes

[This one just came in...]

We knew they were a little batty and wanting in the IQ area, but look at the people who "signed" this thing... Dean Martin? Shazaam?

[Here's an announcement for a project many friends of mine are involved with. Cynthia Hopkins should be a name known to you from the theatre world -- I know her as having written and sung songs for Mac Wellman plays. Anika is probably the first Dutch woman to sing for an all Japanese (and Dutch) country band -- it's called Konteree Bando (sp?), which is how you say "country band" in Japanese. If you're in the neighborhood...]

Transmsission Projects presents in association with GAle GAtes et al.

Compress Your Dreams

Compress your Dreams is written by Anika Tromholt Kristensen, with excerpts from Finnish playwright Michael Baran's You Don't Know What Love Is.

Choreographed and performed by Anika T. Kristensen and Okwui Okpokwasili.

Music composed & performed live by Cynthia Hopkins. Design by Tom Fruin and Jeff Sugg.

Performance Dates:

March 19 - March 23 , Wed - Sun @ 8 pm

March 25 - March 30, Tue - Sun @ 8 pm

April 2 - April 4, Wed - Fri @ 8 pm

Tickets: $12

Special benefit Saturday March 29, tickets $25 *see details below

Reservation and Information: 718-875-9177

Gallery Hours: Tuesday - Saturday, 12 pm - 6 pm

Location: GAle GAtes et al., 37 Main Street, DUMBO, Brooklyn

As Transmission Projects strives to fuse performance and visual art, we have chosen the unique setting of GAle GAtes et al.'s highly visible gallery space for our venue to allow the sculptural installation to stand on its own as a piece of art during daytime gallery hours.

Our Benefit performance on March 29 will consist of the following ingredients:

-

performance at 8 pm

-

after party at LOW, bar below Rice

-

music by Koosil-Ja Hwang and a-un: Kenta Nagai & Tatsuya Nakatani

-

delicious hors d'oeuvres generously donated by LOW, served between 9:30-10:30pm

-

"The Silencer", a cocktail designed for the evening, the proceeds of which will benefit Transmission Projects

-

raffle, with many exciting prizes

-

Tickets for the benefit are $25 for performance and party, or $5 the at the door at LOW, the bar below Rice at 81 Washington Street, 718-222-1569, www.riceny.com/low

Compress your Dreams - a tribute to silence, is a story about a woman's isolated travel in repeated patterns in search of complete silence. On a journey through a noisy mind, she discovers that the silence has been with her the whole way... she just forgot to listen. On this journey she meets a personage of herself, embodied in another performer. We follow these women as they walk into the darkness of the north and the brightness of the ice.

It is a journey into an obscure dream world of singing polar bears and saw playing penguins. The piece is inspired by the harsh environment of the north pole. It draws on the theme of ice as a means of conservation and therefore a forbidding vault for the secrets of history, as well as a metaphor for emotional blockage - but a blockage with the potential for metamorphosis.

We hope to see you at our show.

Sincerely Transmission Projects

[I haven't had the time to water my blog for several days now, but I want make sure that visitors here get some good roughage to eat once in a while, so here is a little slab I found on my hard-drive a few days back. Please note that I haven't had time to correct several instances of unnecessary hyphens included in certain words that were automatically hyphenated in my word processor.

This is a very old, unpublished review of an anthology poems that, while clearly partisan -- very heavy into "Language" poetry in those days -- shows how and what I was thinking back then quite well. I wrote my brief essay about Veronica Forrest-Thomson at around this time, as well as one about Ian Hamilton Finlay which first appeared in the St. Mark's Poetry Project Newsletter. This may have been intended for that as well -- I'm sure I sent it off somewhere, was soundly rejected, and decided not to send it anywhere else. Too bad I didn't have a blog then.

Certainly my views have changed on the state of art, etc., and I am not out to rankle anyone with this -- it lacks decorum at points, and I don't see any point in poetry in-fighting on the eve of war -- but I think the method is basically sound, a "defense of poetry" of sorts, and since I was never much of a theory guy it's pretty down-homey, blog-worthy style. I discuss an anti-war poem by John Taggart at the very end.]

Primary Trouble

An Anthology of Contemporary American Poetry

(Jersey City: Talisman House, 1996) $24.95

The latest in the recent bevy of anthologies of American poetry that attempt, in the manner of Donald Allen’s New American Poetry, to bring an “underground” scene to a greater attention is Primary Trouble, edited by Leonard Schwartz, Joseph Donahue and Edward Foster. This anthology is the least satisfying, and yet it may be said to take the most risks by not including any of the “major” predecessors in its contents to concretize a “tradition” which the anthology maintains or realizes. As a result, however, the burden of telegraphing the main tendencies of the book to the browsing public falls on the introduction, written by Leonard Schwartz, who describes in the following paragraph what the editors thought they saw in, and sought to derive from, the contemporary American scene:

Primary Trouble, then, strives not to define but to draw attention to some of the very latest tendencies in American poetry. While the anthology is in no way thematic, there is a common interest here in a certain vocabulary, a certain set of possibilities towards which these texts have both tended and been chosen. To call this interest “the sacred” would be too officious. To speak of it as “the spiritual” would be amorphous, too easily misconstrued in terms of belief and not imagination, unless “spiritual” be defined as a radical anger with the conditions of the world, socially and metaphysically. Or else it might be conceived as a critical detachment from the given – a detachment creative of the otherness of clarification, of a complex emotional and imaginary spark in the light of which metaphor and reality are constantly in question. To call it a new eroticism would also be reductive, but surely this poetry has an ample category for pleasure, a category absent, as Joel Lewis has noted, in the hegemonic mode of experimental formalism known as language poetry: this poetry sees sexuality as a crucial nexus between the body and the world, one that defies but revivifies words in their very effort to render erotic impossibility.

In this paragraph, Schwartz moves toward vaguer statements while operating within a rhetoric that makes it appear he is fine-tuning his enunciations or attaining a greater subtlety of thought, a tactic which becomes clear when the term “spiritual” is discarded for being too “amorphous”, and yet at the same time is vulnerable to being “misconstrued” as something specific (understanding “belief” to be religious belief, which he clearly wants to avoid), and then is finally replaced by the equally amorphous “radical anger with the conditions of the world”. Descriptive phrases – some of which are decidedly divorced from anything that appears in the volume, such as “a critical detachment from the given” (unless this describes the dream-speech argot many of the poets employ) – are proposed but then quickly withdrawn, or in one case finds its justness in the approval of another – “Joel Lewis has noted” – without a quote or elaboration, as if this were enough to settle the dispute that “an ample category for pleasure” has been “absent... in the hegemonic mode of experimental formalism known as the language school”. (This “ample category for pleasure” eventually becomes plain “sexuality” and then “erotic impossibility” later in the sentence, with no comment on the gaps between these rearticulations.) Postmodernism, uncomfortable with stable definitions, may be at work here, but the paragraph’s awkward errancy points more toward the need to circumscribe a set of ambitions – some of them purely contrary rather than positive, as the italicized “this” in the final sentence indicates – while not falling into the trap of appearing partisan.

Schwartz’s inability to manipulate terms becomes clear with his contention, earlier in his introduction, that the language poets have an “agenda for poetic hegemony”, a statement that is impre-cise and unfair – imprecise because innovation in the arts, whether Abstract Expressionism or Cubism (or eighteenth century English neo-Classicism or the “variable foot”), always produces more work of a second-rate then that of the innovators, thus making the entire aesthetic orientation appear misguided, and unfair because he is re-cording an injustice without providing the evidence, thus creating no more than a general feeling of ill-will and furthering the need to misunderstand. Does the editing of journals, the statement of goals, the creation of new terminologies, the explorations of new tradi-tions and of new forms of writing constitute an “agenda for poetic hegemony”? This agenda is certainly worth uncovering if it exists (it is, ironically, this type of uncovering that characterizes Charles Bernstein’s criticism in Content’s Dream and A Poetics, the type of research which provided many of the ideas that galvanized the mo-tivation for change in poets during the mid-seventies). Criticism of any artist or school is beneficial provided there is data and a speci-ficity of analysis to support contentions, and a desire to produce options rather than adopt authoritative poses that feed off a general discontent, but which mask a lack of substance behind apparent subtleties. When a “new way” is being predicted or anticipated to the detriment of an “old way”, it seems especially important to give the previous paradigm a thorough and illuminating consideration, and to provide the data, which means “new” poems that help one imagine and understand why a shift is in order.

Schwartz doesn’t provide these terms or analysis in his intro-duction, but rather his ideas revolve around a few general concepts of “eroticism”, “mythic vocabularies”, “category for pleasure”, “epistemological rigor”, and “radical anger”, all or most of which, one presumes, is present in the selection, a selection which, conse-quently, is not to betray an “agenda for hegemony”. Consequently, this paragraph, as does the entire introduction, seems to call for a return to a “universal” set of values while maintaining the pretense of newness and oppositionality, but it never, at the same time, dis-tinguishes itself from the aesthetic and political values of the estab-lishment – whether literary or political – which the avant-garde usu-ally subverts on some level. This makes it appear that the “radical anger” described in this introduction is only to be leveled against other poets, which is disappointing if true. It is also worth noticing that the only thing that separates many of the writers included in the anthology from the writing of the sixties and from the main-stream writing of such poets as Charles Simic and A.R. Ammons (who could have been included, were they younger), or Jorie Gra-ham or James Tate (who certainly assimilated much of the “New American” poetics), is their very experience with the writers and ideas of the language school, uncomprehending or unsympathetic (or undesired) as this experience is.

If there is one tiny piece of dicta that is worth resurrecting from Pound – the language of it has not aged terribly much – it is this: “It is better to present on Image in a lifetime than to produce voluminous works.” This phrase is useful in attempting to spot a “poetic hegemony”, for based on the smallest level of the word-event, the image, it would be very difficult to prove that there isn’t a poetic hegemony operating throughout most of Primary Trouble. An example of a few great lines of poetry compared to many of the lines of poetry included in Primary Trouble is worth, in this case, hazarding, for there isn’t much within the anthology that is unusual or excessive enough against which to gauge the general tenor of the writing. The following is from a sonnet by Hopkins:

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame;

As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell’s

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves – goes itself; myself it speaks and spells;

Crying What I do is for me: for that I came.

Hopkins serves the purpose of being a poet who is spiritual and not allied with any artistic movement or avant-garde, and yet who quite obviously has taken pains to radicalize his language. One might, indeed, understand Hopkins to stand for many of the values that Schwartz promotes in his introduction – even the “eroticism” and “rigorous epistemology” find their representation – and yet he equally satisfies the call for an intensity and fullness of language, not choosing to hide behind ellipses and mysticism. Lines from another poet, John Ashbery, demonstrate how a this aural intensity need not be sacrificed when satisfying a hunger for contemporane-ity (this is the opening to “Daffy Duck in Hollywood”):

Something strange is coming over me.

La Celestina has only to warble the first few bars

Of “I Thought about You” or something mellow from

Amadigi di Gaula for everything - a mint-condition can

Of Rumford’s Baking Powder, a celluloid earring, Speedy

Gonzales, the latest from Helen Topping Miller’s fertile

Escritoire, a sheaf of suggestive pix on greige, deckle-edged

Stock - to come clattering through the rainbow trellis...

Image follows image with differing degrees of authorial intrusion, but it is worth noticing the near-physicality of the rhythms them-selves (as in Hopkins), the syllables rolling over each other like waves, the metrics of each line fulfilling and developing upon the expectations of the previous one, with precise shifts that can slow a line incrementally – “Helen Topping Miller’s fertile...” – until it must explode past the enjambment. The variety of the images and rhythms in these poems – along with their lack of theoretical jargon and philosophical circularity – are worth keeping in mind when reading Primary Trouble.

The following are lines from different poets in the anthology who utilize a vague surrealistic language that hints at a nascent “spiritualism”, but which nevertheless has yet to attain a fullness of expression:

Who sees

all breathing creatures

as self, self

in everything breathing,

no longer shrinks

from encounter.

*

the long shadow

of a walking stick

stretched across the desert

warm blood drawn

from the neck of the beast

tales from the withered arm

the dried-up cup

that speaks in small flames

round the rim

*

branches abroad

a memory only

for moods

fail to recognize

a difference

nothing also

has a face

*

Closest,

restored sections of

what is farthest

late drawn borders

re-examined

pulled out as “cuts”

(resistant

that tiny sweet “heart” of

oxygen’s nerve)

*

these are the unspoken details

born out of so many days

walking

the vanishing skies & what follows

as the rains close in

thomas, why have you come so far

to hear so little

For many, and one assumes for the poets themselves, these lines may be evocative, and yet there is a lack of specificity – of signa-ture – in them that eventually hinders interest. A homogeneity is demonstrable in both interests and expression, all of these excerpts establishing an air of anticipation and insecurity, of a strangeness that could be this or that, but never solidifies, the hands left to con-tinue groping along the wall. This makes the reader wary that the air of uncanniness may simply be the poet’s discomfort with the actual idiom in which the poem is operating, as if the poet were merely maintaining a distinction from, say, diaristic or confessional modes of writing, and describing the struggle to do so. What is interesting is that nothing is fixed upon as even possibly coming into view; the writing is so caught up in the possibility of perception, that the terminology appears to be based in a pre-existant dis-course, rather than in the lived trauma of a suffering being – the mode seems academic. The “thomas” included in this last excerpt is an event, especially when set against the ubiquity of the “radical epistemology” which seems to make imagery – and humor – meta-physically impossible. The poetic line is basically “speech-based”, and yet speech itself, with its spastic urgencies, never intrudes to modify what is often a safe repetitiveness. As for the “category of pleasure”, one is unsure from which quarter that is supposed to ar-rive.

There are, of course, many poets in Primary Trouble who don’t write like this, though an inordinate number of them do at some point in this selection. Will Alexander and Dodie Bellamy, two writers who at their best overwhelm with their imagination and willingness to risk linguistic and psychological overload, are pre-sent. The choices for Joseph Ceravolo, especially “The Crocus Turn and Gods” from his long poem Fits of Dawn, are excellent and stand out with their confidence of aesthetic. Two long pieces from Clark Coolidge appear, but they are not as polyphonic as his best writing, and bland in their vocabulary and word combinations – odd, because Coolidge was motivated early in his writing by the need for a new vocabulary in poetry. Joseph Donahue, in the po-ems included here, appears haunted by Ashbery’s idiom, especially in these lines from the poem “Desire”:

It’s someone else’s dream

this bewildered amusement left on your tape

the surprise party the world has arranged for you

and your life passes and you wait for the secret call

when the guests have arrived, you wait for

the one who will intimately mislead you through the rain.

Donahue’s poems are, nonetheless, careful and various, especially “Transfigurations”, which works with a shorter line. William Bronk’s poem-preface, “The Nature of Musical Form”, is a nice little piece of work, but he is one of a number of the poets in Primary Trouble who doesn’t seem to experiment at all with language be-yond the idiosyncrasies of his personal idiom. Virginia Hooper is another example; the following is from her poem “Drawing Room Drama”:

Concealed in the style of a late manner,

It was the spectator hiding behind the curtain

Celebrating the discrepancy

That the context of action conditions the illusion.

The desire to explore has tainted the evening

With a noiseless rush of jazzy agitation for three nights running.

Hooper’s writing is promising, but at this point it appears to have taken its terms – again – from Ashbery, though she has substituted the detail and humor in his poetry with abstractions and Chinese-box-like statements – “the context of action conditions the illusion,” for example – that begin to lack invention. Susan Howe’s “Thorow”, included in Eliot Weinberger’s anthology three years ago, makes an appearance, and one wonders how a reading of her work suffers by its inclusion among other poems that are derived from her style though without her use of ballad-like rhythms or her scholarly intellect. (Both she and Nathaniel Mackey – strongly rep-resented here – have developed a poetics that are derived directly from readings of Olson and Duncan, and yet they are each exam-ples of how some of the ideas of the “language” writers have given both definition and substance to the aims of the recent generation.)

Ronald Johnson makes an appearance with sections from his long poem Ark, which has just been published in its entirety; he is a maverick of sorts, not conforming to any easy rubric, and much of his writing can be beautiful, though oddly static. Bernadette Mayer and Eileen Myles are represented, each not quite satisfacto-rily, the Mayer selection devoid of the color, liveliness and inven-tiveness of her best work, and Myles having only one poem. Claire Needell’s very short poems are interesting, and brief enough to quote whole; the poem “Propagation” runs: “I want you to think / me hollow. Intercourse suggests / an artificial point”, creating a conundrum of body and syntax that doesn’t flow into overelabora-tion. Alice Notley and Geoffrey O’Brien are both strongly repre-sented, as is Michael Palmer, whose poem “Untitled (September ‘92)” makes use of the “sacred” theme, but while utilizing the entire arsenal of techniques available; it begins:

Or maybe this

is the sacred, the vaulted and arched, the

nameless, many-gated

zero where children

where invisible children

where the cries

of invisible children rise

between Cimetiere M

and the Peep Show Sex Paradise

Gate of Sound and Gate of Sand -

One is often not sure how much Palmer is merely engaging in art-culture games, using his talents for no more than picture-books, but this poem demonstrates his ability to create waves. David Shapiro’s poem “Archaic Torsos” (one of Clark Coolidge’s poem also takes off from this theme of Rilke’s) is a sonnet that begins “You must change your life fourteen times”, and which proceeds to do that, ebulliently, for its duration; the rest of his poems here are otherwise pretty standard for him. Gustaf Sobin’s work derives from a basic theory that the sound of poetry is a tunnel into some sort of tran-scendental awakening, but many poets, including some in Primary Trouble, explored this theme more thoroughly – Olson, Duncan, Coolidge and Mackey have made similar investigations – so that he appears derivative. There are other writers and poems worth look-ing at in the anthology – Ann Waldman, John Yau, Lee Ann Brown, Robert Kelly, Myung Mi Kim and Ann Lauterbach are also included – but strangely enough the selections from many of these poets are flat, and one suspects that there has been an effort by the editors to purposely exclude certain poetic practices even when the individual poets embraced them.

John Taggart’s poem “Twenty One Times” is one of the few poems that take up a social theme, and is worth considering in some detail, for it points to some problems with the editorial pa-rameters of the entire book. The poem is centered around a refrain of the word “Napalm”, and the first four of its verses run:

1.

Napalm: the word suspended by a thread

the word grows as salt crystallizes

I will grow cells of the word in your mouth.

2.

Napalm: leaping as if wrought in the sea

leaping as if pursued by the horse and his rider

a young hart a young heart comes out leaping.

3.

Napalm: rub the new-born child with salt

“the fault is that we have no salt”

if the master’s word is taken the salt is love.

4.

Napalm: soap will not wash the word out

the word breaks through partitions and outer walls

breakthrough of cells of the word in the mouth.

There is something about the refrain of “Napalm” that is discon-certing, especially with the allusions to the salivation that accom-pany repetitions of the word, as if this attempt at exorcism were really an excuse to reinvestigate and reestablish his relationship – very “erotic” it appears – with the word. To publish a poem using “Napalm” as a refrain in the present decade exhibits not only a nostalgia for a time when poets sense more clearly their class dis-tinction from the establishment, and hence could be self-righteous and hieratic, but also for a time when the American government was at its most actively militaristic, engaged in a warfare that deci-mated an entire country, regardless of the prophetic and spiritual agencies of these poets. One is free to make poems out of any subject matter one wishes, but Taggart’s poem – technically sophis-ticated, full of apocalypse, yet elusive in its specific meanings – re-mains, like many of the poems in this anthology, caught up in its own machinery, deriving its main social value from the the “jellied gasoline” – the “blackbird” in this poem that owes much to Stevens. Does this poem recognize its debt to atrocity, and intend to insti-gate a change in thinking? does one care how many times “Na-palm” can be perceptually reconfigured in a poem, and is it valid as a method to take this word and investigate it for its aural and evocative content? is this an adequate way to record history, and to warn of its possible recurrence? These questions, which exist at the intersection of art and politics, have been further complicated not only by the innocuosness of a the contemporary hieratic mode – based on modes of the sixties but lacking its danger – but by the various revolutions in information technology that render the poet’s task of getting attention more difficult. Since most of the poems in Primary Trouble cannot be said to represent the “latest tendencies” in American writing – especially since the editors have purposely sought to erase rather than confront the achievements of the most innovative practices of the last two decades, that of the language school itself – the very parameters with which one can begin to in-vestigate these questions are not even present in the volume beyond the ambitious terminology of the introduction.

[Hey, I haven't had time to post anything to this blog for the past several weeks, so I'm hunting for material from my hard drive. Here's the text of an e-ticket I purchased (or that was purchased for me) for my trip to Detroit in, uh, November?)]

Issue Date:

27AUG02 NW/KLM Reservations

1-800-225-2525

www.nwa.com

Attn: MR BRIAN STEFANS Confirmation Number : 765L2H

Day Date City Time Airline Flight/

Class Status Meal/

STOP Seat(s) Equip

MON 11NOV

Leave LAGUARDIA

Arrive DETROIT

415P

614P NW 0261K OK

0 STOPS 20C 755

WED 13NOV

Leave DETROIT

Arrive LAGUARDIA

702P

856P NW 0538K OK

0 STOPS 08D D9S

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Passenger List: BRIAN.K STEFANS MR

Your trip has been adjusted to the itinerary above due to a change in our schedules. Please contact Northwest Reservations at 1-800-225-2525 if you have any questions. We apologize for any inconvenience this change may have caused.

THANK YOU FOR FLYING NORTHWEST/KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I haven't blogged in a while. So sorry. I don't even have any off-hand cheap-o poems or writing to toss up. Sorry again.

Here is the rough table of contents to Arras 5, a double issue, to gnaw on for a while. Each is roughly 96 pages; both should be done in about a week!

arras 5 part i

Featuring poetry and plays by Darren Wershler-Henry, Tim Atkins, Edwin Torres, a. rawlings, Gregory Whitehead, Kevin Killian, Brian Kim Stefans, Jordan Davis, Kent Johnson, Reptilian Neolettrist Graphics, Mara Galvez-Breton; essay by Katherine Parrish

arras 5 part ii

Featuring poetry by Kevin Davies, Katie Dagentesh, Ira Lightman, Carol Mirakove, Christian Bök, Gary Sullivan, Dagmar's Chili Pitas, derek beulieu, Jessica Grim, Kenneth Goldsmith, Robert Fitterman and essays by Alice Becker-Ho and Darren Wershler-Henry

Other news: Fashionable Noise is finally almost off to the printer -- just a few typos on the cover to fix; I'll be on the insulin pump probably by the end of next week; I'm going to San Francisco in April with Rachel to visit my sister (and mother who is visiting my sister long-term) and the wee niece Natalia; working on .pdfs of Bruce Andrews' political writings which I'd also like to get up by the beginning of summer; what else; I'm being interviewed by the Iowa Review Web for their May issue which will feature "me" a bit too prominently for my taste (a review of FN will be in the issue); I've also been given the green light to write an essay on John Wieners for the Boston Review, but it won't appear for nearly 8 months; the Circulars hit count has been peaking at 3,000+ a day (roughly) and the site is due for some upgrades (search engine just added); I'm still broke. Thanks for asking...

(For those of you who like to be amazed, I'm listening to Radiohead in the office right now...)

[Here's the manifesto by LRSN that my Stigma 2001 manifesto was based on...]

We in the last quarter of 2001 affirm the following guidelines for the publication of literature, patterned upon the manifesto of the Dogme95 filmmakers. The Dogme95 Manifesto declared itself to be a "VOW OF CHASTITY" from the coercive representational techniques of mass-market cinema (sets, lighting, musical soundtracks, etc.); Dogma '01 goes even further, rejecting the no less coercive marketing and distribution apparatus which Dogme95 filmmakers seem content to have deployed on their behalf. Dogma '01 rejects the division of labor between writer and publisher that prevails in the literary market-place, and therefore its productions are unfit for all but the most informal modes of distribution (barter, give-aways, and low-volume sales). These rules are to ensure that they remain so:

1. Dogma '01 is unalienated labor. Author and publisher will ideally be the same person. If not, they are to share the labor and cost of printing. Dogma '01 productions are to be assembled and bound by hand. No sending books out to be Docu-teched, and no perfect binding.

2. The contents of Dogma '01 books should be photocopied. Type may be set on a word processor or typewriter, but handwriting (the textual equivalent of the hand-held camera mandated by Dogme95) is best. No technique of reproduction is definitively barred, but those methods and materials most widely available to the general public are preferred. What in the world of fine printing are considered defects, Dogma '01 views as beauty marks: staples, thumbprints, "binder's creep," etc.

3. The one-of-a-kind is hateful. Editions should be as large as humanly possible, unsigned, and un-numbered (except perhaps to compensate for the flaws of "first fruits" rush-jobbed in time for a reading). Scarcity should never be exploited to drive up exchange value. At such time as an author's Dogma '01 publication turns out to be a valuable commodity (i.e., quickly reselling for inflated amounts soon after issue), that author is obliged to produce ever-larger editions to compensate. Should demand exceed the author's production capacity, that author is obliged to withdraw from Dogma '01 and either go with a mainstream publisher, or become one. This is the only excuse for going with or becoming a mainstream publisher.

4. Publishing in journals is kind of a gray area, on which we do not care to pronounce. Without it, Dogma '01 would risk becoming a solipsistic enterprise, with a readership as tightly circumscribed as that of any corporation's report to its shareholders. On the other hand, the wider an author's public, the harder it will be for that author to remain within the bounds of Dogma '01. The same goes for anthologies. Nor have we come to grips with the question of later reprints of Dogma '01 productions. Entering contests is fine, unless you win one.

5. Dogma '01 is not a bid for elite/outsider status, but the affirmation of a literary and artistic sphere of exchange unmediated by the apparatuses of market capitalism. (Except does the post office count?) Authors need not lose money to qualify, though they assuredly will. Dogma '01 authors are to maintain cordial and friendly relationships with mere writers. No Dogma '01 clubs or juries are to be formed, and no one whose work meets these Dogma '01 criteria is barred. You will know it when you see it.

Dogma '01 is no guarantee of quality. Without going so far as to abolish the category of "artistic merit," it is our stance that 1) the above criteria are more important at the present moment in the history of writing, and that 2) they lead to better work anyway aesthetically as much as ethically speaking.

Please note that the above rules cannot be bent to include unqualified authors whose company and fellowship we may covet. For example, the book "Scram #2" by Mark Gonzales and Cameron Jamie with Raymond Pettibon photocopied in a signed and numbered edition of ten and sold for fifty dollars apiece last year at a gallery in Hollywood cannot be claimed as a Dogma '01 production. (Too bad, because it's the summit of the half-sized booklet form.) It will also be noted that Dogma '01 is hard for novelists and writers in non-fiction genres, though we would be delighted to see someone try.

You are invited to reproduce and disseminate this manifesto freely. We will not rest until the earth is encased in a rustling jacket of paper. Oh wait, that's already happened.

Oakland, Calif., 10/6/2001

On behalf of Dogma '01

LRSN

This blog makes it sound like there's a whole blogging culture in Iraq -- heard anything about this? I haven't done any research on it myself. Is this a hoax?

http://dear_raed.blogspot.com/

[Once again, I'm refraining from commentary as I'm about out the door, way too tired -- had drinks with John Wilkinson, Bruce Andrews, Marjorie Welish, etc. yesterday after Craig Dworkin's reading at "A Taste of Art", not too late but did have to be at work by 9. So here's a post from Patrick Herron of Lester's Flogspot and proxmiate.org fames and other fames -- just noticed that I don't have his blog on my blog roll, but will soon.]

"The Creeps wonder why, in a culture that has public enthusiasm for artists like Matthew Barney, Ornette Coleman, and Cindy Sherman, all of whom are taken to be defining cultural figures of their time or at least "artists," poets who are similarly disruptive and experimental are often not noticed, and not missed. They wonder why the poetry world is not as interested in the "edge" as the art and music worlds.

They don't consider themselves outsiders, the "marginal," and hence never of any use to mainstream thought. On the contrary, they take interest in many of the greatest debates of our time, particularly over globalization, cultural memory and the goal of human agency. Their distinguishing feature from writers from the mainstream, and also the writers of "Elliptical" verse, is that they expose, are exposed, and do not recognize any glass ceilings in terms of what can go into a poem, nor some safe, predefined notion of the "self" as their subjective limit."

Disruptive. De-egoized. Anti-manifesto. Concerned with information overload & technology. Challenging notions of self. How to synthesize agency with post-structuralism. Wondering where the edge is in poetry. Finding barriers just to dash them to bits.

You know, this really nails it for me personally. Particularly in my efforts to get Lester's _Be Somebody_ published (the book is on one of the CDs I gave you). I've been having an extended discussion with a well-respected poet and writer about Lester's book, that it toys with the notion of seducing the reader. The book gets perhaps downright unfriendly at times. I mean, seduction in writing is something I'm personally into, but it is nonetheless a will-to-power author-dominance function that maybe could be criticised in just one damn book of poetry? Just one? And that's what Lester wanted to do--challenge the assumptions of author-dominance through gestural play of linguistic dominance and submission, and still remain somehow poetic. Poetry seems more than any other literary field to depend highly on the AUTHority and AUTHenticity of the AUTHor. In retrospect Lester's book is a sort of 4th stage Baudrillard, all simulation--simulation right down to who the pronouns reference. A simulation of getting personal. A simulation of authorial integrity and authenticity. Gestures towards the book itself (repulsion) invert the author-reader hierarchy. And so on.

And interestingly the other half of our discussion about the book regarded its use of longer fractured lines. I don't write that way so much anymore, but I did so quite heavily two years ago. Trying to cross Spicer with Whitman, Ginsberg, and Giorno and turning blue in the process (blue emotionally and physically). I felt I had to sort of defend the practice, you know, and explain about shifting frameworks & subjects, and the way such writing speeds over a sonic, imagistic and/or logistic landscape. There's not a great deal of the longer-line form in the book, but it, like so many other tropes, sticks out when set against its context not only within the book but in the context of the po-world.

Some very big ups to this writer-friend of mine--one of the things I did not have to defend was the relative lack of "poet's voice"--he rather enjoyed the looping structures and widely varied poetic tropes. The post-modern aesthetic doesn't have to be defended. Some of the less readily apparent syntheses of subjects and formal issues and critical theory, however, do require such defense. Your statement helps take the pressure off me a little.

Mostly though it's gotten very good responses, and all of them at least have been strong, whether in favor or against it. And it has definitely been disruptive. And it is certainly obsessed with information. I am scratching my head, now realizing I finished writing that book in 2000. And it still does not exist--you know, the proverbial tree falling in the uninhabited wood. C'est la merde.

So perhaps I should not admit it but you might have me pegged too. Or at least have Lester pegged. The "danger" with pegging Lester is that he's a parody of himself in his "frank-talking" way. He's not above his own criticism. He was already parodying the info-hound mode back in '99 and 2000. And maybe he still does. He's more interested in testing the divide between a poet and hir poetry, a sort of zen whipping. But I think you compensate for and encompass that possibility in your essay, too.

I'm not so curious anymore about why poetic edgework is not considered relevant, though I was maybe a year or two ago. I realized a few months back just how much poetry is a burled wood and 30 year old Port-meets-Ben Shahn pursuit, a profession that is dominated by the over 40 settled class. Painting and music and photography professions all realize that creative genius generally peaks in the mid to late 30s and they don't want to miss that output when it's happening. They capitalize on youth and trade on youth. (It's not above criticism; we all know the art and music worlds exploit that youth frequently.) Poets are much more conservative and much more dependent upon authoritative critical opinions. Those opinions happen to move much more slowly in the po-realm and are less widely distributed than in painting, music, photography. Poetry perhaps also potentially poses a little more of a cultural/political threat than music, painting, photography. Language is very immediate and dangerous, unlike images, (words can conjure non-imagistic ideals, rallying cries, etc.) but the poetry industry ensures all must come through them and slowly accepted before even a trickle is to come through.

When we look at the lives of so many poets, they were nobodies up until their late 30s and each gets a sort of big break or phat association or something. Olson was a nobody when he became Rector at BMC, just to give one example. And he at least had Ivy on his wall to make it easier for the authorities pick him. I think something like only ONE poem of his was published before he became rector. That sort of visionary foresight exemplified by BMC is of course still delicate and rare, perhaps even moreso fragile and infrequent today. I dare say there is NO modern-day equivalent.

Shit, even radical improv music listeners have WIRE to read; artists can read Flash Art; and so on. But poetry? What, POETS & WRITERS? I had a gift subscription to that for a year, and every time I received a copy in the mail either it was already covered with cobwebs or someone's set of false teeth fell out of it. It was so incredibly fogey and safe. Full of saccarine platitudes about the lives of writers. I developed back pains and grew gray hair just in reading the first issue. It's OK to be fogey, but why be fogey to the exclusion of youth?

The study of modern american poetry is the study of settled aging people. We young poets are apparently not mature enough; we too are told to wait like everyone else to be published. Yet it is difficult to imagine that I will have anything left in me by my 40th birthday.

Chris Stroffolino's had the same sort of experience that Lester has had; having the "nice" stuff published while the more confrontational work languishes. And I think he's struggling to have his most recent book published, which is absolutely absurd considering how good his writing is. Art in poetry languishes.

And yeah, performance too...it was fun to read with Lee Ann last year because we both will do some sort of singing when reading. Shamelessly entertaining but what else can we do?

I even don't mind having Thom Yorke (the requisite pop-cultural figure) as a referent in the naming of this. You know, two years ago, so much of the sensibility of Radiohead's "OK Computer" really summed up so much of my own will to articulate. That album formed a sort of musical representation (a very incomplete one) of some of my feelings at the time.

Okay, I'd personally dissent with some minor points of your essay: I guess I'm very much FOR community BUT against "interactivity" (which is a sort of proxied intimacy and anti-community in some respects), and devoutly committed to epistemological issues. I can't separate heteronymity, notions of self, ambiguity, poetic artifice, and barrier-breaking from epistemology. The very necessity for a heteronym is an epistemic consequence of my own personal experience of the act of writing, or, rather, my non-experience of it. I don't think that really creates any sort of problems for what you wrote, however. You're describing a landscape that describes my yard. Just because my yard might have a patch of sand here or there doesn't preclude it from being forested.

I have to admit that at the same time I am a huge admirer and ardent reader of manifestos I also remain highly suspicious of them. Manifestoes require yet another hierarchy, and their concomitant big egos. I rather like the workman "play the part on a team" aesthetic implied in your essay. I don't see the serializeable and substitutable parts notion as a consequence of capitalism: communist countries used interchangeable parts as well; they have factories (look at China). Anarcho-syndicalist organizations might have production lines as well, just so long as participants 1) have a sense of humor about work and 2) are legitimately vested in the produce of their labor. I rather like the flexible anti-hierarchical structure implicit in your notion of the Creep. And even if such a structure is capital-derived, then it can co-opt, outpace, and overcome the problems of capital by its very nature of subjugating capitalism's needs. Why be so puritanical? Given the Darwinian flavor of Marx's writings it makes little sense to advocate leftist revolution, even in art. And we all know how ugly right-wing revolution is (look at America in the here-and-now).

Kasey's analysis in a certain way makes your position more attactive, not less. You see, being invisible and flea-like as a writer ain't so bad. It's anarchism and anarchism requires that people voluntarily come forward to do what they love, to play their parts. It kind of, um, clips the wings of those who feel the need to dominate others. It cuts down on the asshole factor. Assholes might be found in golf shirts making corporate deals on cell phones in their khaki dockers, but the assholes might also be dressed in hemp pushing print versions of their revolutionary manifestoes. The asshole factor is everywhere someone or other wants to dominate, lead, or didactically instruct.

So many things in your essay resonate. It's folks like you who make a huge difference to poetry. Well, you make a difference to me anyway. Keep it up.

Patrick

[I've been mucho busy and can't put in appropriate links etc. a la Ron Silliman but here's an email I got from Geoffrey O Brien regarding my Loose Notes on "Creeps" and the Stigma 2001 "manfesto" which are both locatable via the sidebar.]

Dear BKS:

just wanted to say that i loved your spoof of LRSN's Get at me Dog '01, tho i found it light on the spoof and heavy on the transferred application (not a quibble, a gladness). here comes the inevitable however/but/yet/also. however, i wanted to respond to both 3.3 of it and one of your points about Moxley (both quoted at bottom of email), which i think share an assumption i'd like to trouble slightly.

it seems to me that "th inr sanctum of th author's memry and sentmnts" (why didn't you alter "sanctum" or "author"?) is/are the ultimate repository of FOUND TEXTS and would remain a useful part of poetic practice if the things found there were not seen as "stemming" from a space but as repottings of nonspace (or some other gardening metaphor i've avoided knowing). poetry isn't about losing or recovering affect within content choices and avant-garde reuptakes so much as it's about DETERMINATIONS on the form-content axis, a point you quite rightly make about Moxley in re her relationship to particular precursor texts and historical style-moments.

in this sense, how Moxley feels towards her practice (which itself "feels" towards myriad other practices) carries affective charge, and so does anything by Jackson Mac Low or Christian Bok for that matter, since their choices/subsequent determinations vis-a-vis dominant and marginal practices (both past and present) graphically, flagrantly constitute their texts.

There is no poetic material that is not already a transformation and, for me, no transformation that is without history, no history without affect. Not to mention the charge of devaluing time itself by running it through the author and reader function where not very much money, even in LRSN's hated perfectbound economy, changes hands (the same can be said for transactions in virtual country).

Moxley's poetry seems to me, as limit-case, to express the inadequacy and narrowness of the found text concept or to limn it in a humility it neither deserves nor needs. Her text is certainly found and it carries affective charge bc we read its oscillations in re its own discoveries, and in part bc there isn't a single source or sanctum but only, and ultimately, an unquantifiable texture, a set of readings, or Barthes' Text (tho why he capitalized i'll never know--it's always seemed to me like trademark protection), which "here" we can call I/you/we/they-reading-Moxley-reading-Victoriana or a recombinatorial host of other names. or we can call it nothing at all.

i'm taking many shortcuts here, but you inspired me to say a purposeful hello. and thank you for Circulars, another great found text.

best,

Geoffrey G. O'Brien

[In the interest of found art, web avatars, chance procedures, self-googling, and the all-around Ashberian culte du moi, I post the following two poems by people who share significant aspects of my name from the Poets Against the War website.]

David Stefansson

29 years old

Reykjavik, Iceland

bio: Two published books of poetry, 1996 and 1999.

Upbringing, Mr. Bush

Tell me

just this

one small

thing:

how

am I supposed to teach

my children

tolerance?

[If I may venture an answer: try googling your name at Poets Against War and reading all the poems that come up that you haven't written! -- bks]

Brian Kim

15 years old

Seattle, Washington

bio: wassup...im brian...this poem was for english class...

My Prayer

This nation should not go to war,

Because we want less death, not more.

We aren’t sure what kind of weapons he has,

He could have nuclear missiles and gas.

President Bush does not have a clue,

I think he’s got a bad case of the flu.

Our nation has to be real smart,

Because in one decision, it could all fall apart.

War will not accomplish anything,

Saddam will still be hiding many things.

He’ll do anything to cause harm to others,

But let’s not let that happen; protect our brothers.

Preventing the war will save millions of lives,

So let’s do our best and keep others alive.

Whatever is done, will be in God’s will,

So let’s just pray, that not one will be killed.

[I think this poem is quite good until it gets to the "brothers" and God stuff -- but after all, that's closer to the language of national policy than most of what us "poets" put out, not that anyone's listening, to me or to Brian "wassup" Kim. -- bks]

[Here's the first 20 of the Proverbs of Hell (Dos and Donts), chunky paragraphs of 575 letters each about web poetics, that are appearing on the inFlect site. Someone somewhere on some blog out there, perhaps Jonathan Mayhew, wrote that s/he was thinking of Blake's Proverbs a lot lately -- maybe proverbs are in this belle saison d'enfer. I don't have any new content for the blog today except a little note on the Kiki & Herb show I saw last night at the Knitting Factory, which is forthcoming.]

1. In seed time learn, in harvest teach, in winter enjoy. In off-hours at work, visit jodi.org for pro-situ distraction and turux.org for preter-semiotic action in game-world real-time. In hotels at conferences on digital poetics, avoid the theorist who would be five minutes past seed time and has reaped five critical harvests from the postmodern American novel. In the disquieting sempiternality of a north-northeastern winter, enjoy nothing more than the liberation from the ill-effects of prolonged programming and the overripe prose of intelligentsia flame wars. Behave not as if the abs had the shelf-life of your Athlon. In seed time learn, in harvest teach, in winter enjoy.

2. Drive your cart and your plow over the bones of the dead. Drive your internet app through a cartload of high-res images drugged by the uncompressed plows of B-techno sound loops, and you might chance upon the gold filling of a retired army general in your pasta al dente. Drive your viewer through too many randomized texts masquerading as aleatoric derive, and you shall find a reader with a bad hair life. Drive not at all, but walk blissfully in the carnivalesque bubble malls of suburban psychogeography and mingle with the buxom banes and lustless lux-loves not screened since the time of Neuromancer, Kora in Hell and Paris Spleen. Drive your cart and your plow over the bones of the dead.

3. The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom. The road of greater flexibility in method of random access and greater variability in the contract of approach leads to the simplicity of the modemless codex and the finger-panning of the papyrus scroll. The road of suggestive variability is the road to multimedial beauty; the road of arbitrary personalization is the road to unilateral disinterest and the hypertrophy of exchange. Provide the user what she seeks in curious synaesthetic doses and you shall taste the wine of unpassive attention — a little "fort da" never hurt anyone. Fake not the myth of access to palliate tunnel vision. The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.

4. Prudence is a rich, ugly old maid courted by Incapacity. But more users have visited Prudence's web page than Exhibitionist's, because Capacity has become the mantra of the Electroconomy Global Theme Park. It is the Artist who pulls abundance out of CPU Incapacity, and it is the Artist who will not be burned by Dot Com Meltdown. Prudence is a maid whose riches are high in concept, high in pragmatist protein, and low in unsaturated Fats of the LAN. Exhibitionist’s saving grace is that she captures more mp3’s than anyone else, and once bandwidth goes the way of Ptolemy’s shell, she will be the coroner that stole the company wreath. Prudence is a rich, ugly old maid courted by Incapacity.

5. He who desires but acts not breeds pestilence. She who desires not but acts breeds with him. In a male-ruled programming culture, the hunk of the He damns the shank of the She, and the frank of the We chalks the funk of the Thee, and gender politics returns to square one. We who desire cyberbodies dissembling in cloaks of poly-gendered morphs and reassembling the highways of privilege into voodoo potlatches of counterfeit visions of interest — mean business. Avatars are unacted desires breeding the pestilence of drive-by identities, the essence of Self becoming the flavor of Month on a paratactically arranged grid of interacting IPs. He who desires but acts not breeds pestilence.

6. The cut worm forgives the plow. The cut phone line is not a blow, but trusts in the Manichean humanism of c’est la vie. The Life of Action and the Music of Changes are thwarted by ignorance of the varieties of fundamentalist CPUs and modem’s derangement of tout les sens, but surrender not the vertigoes of concept and the fungoes of multimedia to an ignorance of Variable Means and the fuzzy theses of Medium Conviction. Embrace the machine’s inconstancy as one more version of the violence of inscription on the skein of the page, and succor the weak of memory and the short of processor with “feature” not “bug” predilections. The firm course requires this vow. The cut worm forgives the plow.

7. Dip him in the river who loves water. Dip him in the particle acceleration of virtual subjectivities and phantasmagoric geographies who leaps or laughs for the depths of data, and you shall have a better informed viewer of the Jim Lehrer News Hour, if not a better Rortian empath or Pynchonian philomath. Find the well of electronic water, and dip him in; this well is called scandal, and the chemical equation: those you know, squared. Web space must be Rabelaisian or it will not be at all. Bathe the lights of singular attitude in the solipsistic eddies of plural contradiction and you shall have a mouth wet with Wildean puns and Debordian detournement. Dip him in the river who loves water.

8. A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees. So make a new tree for the wise man, a new tree for the fool. The electronic object’s art is expanded tenfold when the same object is variably utile to provide each user discrete, but not exclusive, experiences. Enter the car from the left side, and you are the driver; enter it from the right, and you are a passenger. The electronic object’s art is expanded twentyfold when its contents’ dreams are influenced by the user’s moods, putting fool and wise man in the role of confessor, creator, test animal and personalized drug czar. Feedback is the howl that the fool calls foul and the wise man feed. A fool sees not the same tree that a wise man sees.

9. He whose face gives no light, shall never become a star. He whose light gives facts, but whose face no stare, shall never become a namebrand, but also shall not demand a name. Randomized text, unlike randomized sound, does not absorb, though scores the orb, for the ear sips while the eye winks, and the fingers twitch when the retina slips its lines. For he whose source would become a store, use what words have which neither sound nor image nor code have: reticular nuances that subsume their proscriptive sense. To lie is not to deceive; to tell the truth is not entirely reasonable when the truth is for sale, even if this truth be random. He whose face gives no light, shall never become a star.

10. Eternity is in love with the productions of time. But productions in time that emerge horizontally stand opposite the indifferent verticality of eternity, though eternity signs the checks and the productions cash them, neither entirely satisfied with this cycle of crisis and redescription but both too winded to resist. Eternity shines not nicely on the digital object, which produces no ruins and whose signature absence is a deictic presence. Contemporaneity shines joyously on the digital object, which shares in its bull market confidence and lemming-like capacity to trust in the blue horizon just beyond the last dot of calm. Eternity is in love with the productions of time.

11. The busy bee has no time for sorrow. The cyberpoet has no time for crying over concepts spilled from prior generations, though sorrows that Means were not always up to Minds and that digitization could not rescue Bob Brown’s poem machine from the seams of time. The conceptual poet has no time for others, and the humanist poet no time for robots; the reptillian poet has time for concepts and humans, but cares more for tending fonts and rollovers. The cyberpoem that doesn't “stare back” the more it is stared at is not a good text, not a good app, and not very polite; the cyberpoem that stares back too sweetly devolves into the nirvana of neurobuddhist hype. The busy bee has no time for sorrow.

12. The hours of folly are measured by the clock, but of wisdom no clock can measure. With faster CPU processing, folly has a field day at increasing rates of speed, while wisdom remains a panoramic hologram on the flight decks of the vistaless future. Algorithmic procedures do not liberate one from the variable strictures of singular prose, and one shall not be “Joycean” through Perl scripts that factor Derridean punscapes and Perecois anagrams with the flick of a switch and the indifference of code. Wisdom sleeps in the aporias of folly; folly dances in the “black gold” of wisdom’s over-sized lederhosen. The hours of folly are measured by the clock, but of wisdom no clock can measure.

13. All wholesome food is caught without a net or a trap. To overload a web poem with tricks puts tears in the reticular tarps that are the cyberpoet’s Walmarts and Bennihanas, and scares the wholesome into memory’s entropic sandboxes to mourn the safe havens and sedate mirrors of an ontologically secure youth. The wholesome of site are not inclined to engage digital fluids, just as the wholesome of sight are unaware of the chiaroscuros and arpeggios of crumpled Fluxus bags. Satisfy those who fear the immaterial, and you have satisfied many; satisfy the digirati, and you are a suitor snoozing beside the streams of Herecleitian lusts. All wholesome food is caught without a net or a trap.

14. Bring out number, weight and measure in a year of dearth. Bring out more numbers, some clam-baked action scripts, some aborted lyric doggerel, old Adobe Horrorshop files and scanned pages from Pound’s Cantos in a year of not having many good ideas for poems. Modular web works can shine with the thousand points of light that their centrifugal, contradictory inspirations shed on the fabled ineffability of the art-object’s ontology. Fear not the updating of a Flash file for the fertile episteme of a brave new context, as meaning is extrinsic to the bit as it is to the 17th semicolon in the first sentence of James’ The Ambassadors. Bring out number, weight and measure in a year of dearth.

15. No bird soars too high, if he soars with his own wings. But a cyberbird can soar even higher after mastering the aviary of collaboration. The Auteur in the cyberrealm is the White Magician of the pixelated Middle Earth, yet no Auteur thrives without drinking deep in the River of Borrowed Texts, Borrowed Scripts, and Borrowed Sounds. Even Godard had a cameraman, and Welles never wrote an original screenplay. The role of the bureaucrat and producer becomes the glory of the poet and director when the coordination is of artists and the conversation of production, all on the same platform and each following the same hypnogogic thread. No bird soars too high, if he soars with his own wings.

16. A dead body revenges not injuries. A cyberpoem whose scripts are error-prone, whose ani-gifs break, and whose sound files crackle with the whimsy of renegade bits, may thrive like the Spiral Jetty in the memories of its first historians, but will be deemed unfit for the canons of Les Damoiselles D’Avignon. Fault not the cyberpoet who has made one small contribution even if his reputation be bunk, for the capital that seems corrupt today is the capital that was not here yesterday. A dying cyberpoem tells no lies, yet utters nothing but easy truths. A living cyberpoem tells many lies, but its truths are in technicolor, encrusted with entropic salts. A dead body revenges not injuries.

17. The most sublime act is to set another before you. The most sublime cyberpoem is a digital object with the plasticity of a solid (Rubik’s Cube) or a literary object with the complexity of a database (Ryman’s 253). A digital object should be an ordered arrangement of angles and plains (Vorticism), or a disordered arrangement threatening order (Calder’s mobiles), or a disordered arrangement threatening disorder (Tinguely’s Homage), or two or three of the above. What is set before is also set within in the absorptive scans of the seductive screen, thus putting the v-effekt that much further from touch or placing it too close to teach. The most sublime act is to set another before you.

18. If the fool would persist in his folly he would become wise. If every poet who faltered at the doors of script persisted at least to the finger foods table, a culture could bloom of the Wonders of Attempt, despite the wilt of the Poverty of Completion. Those who cease, sated with unease, or fail to progress, distressed of will, shall outnumber the wise threefold, though the number of fools not increase. Theme music played at a digital literature awards ceremony cloaks not the fool in cultural capital nor demeans the wise for whom capital is a cultural tool, though both the wise and the fool should be spared the folly of attending. If the fool would persist in his folly he would become wise.

19. Folly is the cloak of Knavery. But Folly and the Knave click in a synaesthetic embrace free of the Sorry of cultural dictatorship and the Volly of proscriptive dogma in a world where nation is a code word for corporation and citizen a code word for slave. The digital art project that would be a nation is a notion of the ineffable past, as the digital art project dissembling a citizen sans passport and action sans anthem is a premonition of the porous future, not to mention symptom of the schizophrenic Long Now. Knavery is the glory of she who would choose wisely among the fools, as Wisdom is the embarrassment of she who would choose blindly among the followers. Folly is the cloak of Knavery.

20. Shame is Pride's cloke. Cloak not thy shame in bauds of circuit cholesterol lest the projects of those ten years younger stumble in the frailty of your OOP code and limp in the blushes of your crushing guassian blurs. Cake not thy shout in sentences of eternal shit lest your department research your bibliography and discover Shim’s immortal words among Shem’s expendable ibids. Plagiarism is sweet, and the more the merrier, but the cite is minor when the goal is literature, and digital culture, which claims to be the minority, has no patience for authority when there’s no there there and subjectivity has been mired as mirroring some ivied Joe’s dystopic joke. Shame is Pride's cloke.

i’m

“off”

words

i’m

on

*

seeking

help

for

(in

terrible

space)

suspended

by five

alarms

*

in

attention-

surplus

disorder

*

“bloatocracy”

is not a neologism

(it's a fad)

*

heeeere's geeoorgie!!!

[If you've got a spare 5 minutes, check out the new web piece by jimpunk.com. It's got sound but it's not loud. Let's call this an elegy for a certain brand of techno-futurism, but perhaps for a constructivist ethos as a whole, whether it be the international style, those assembly-line short haircuts or gray browser windows. A beautiful, melancholic mechanical ballet that certainly humbles this "digital poet."]